I just set up SSLTLS on my web site. Everything can be had via https://wingolog.org/, and things appear to work. However the process of transitioning even a simple web site to SSL is so clownshoes bad that it's amazing anyone ever does it. So here's an incomplete list of things that can go wrong when you set up TLS on a web site.

You search "how to set up https" on the Googs and click the first link. It takes you here which tells you how to use StartSSL, which generates the key in your browser. Whoops, your private key is now known to another server on this internet! Why do people even recommend this? It's the worst of the worst of Javascript crypto.

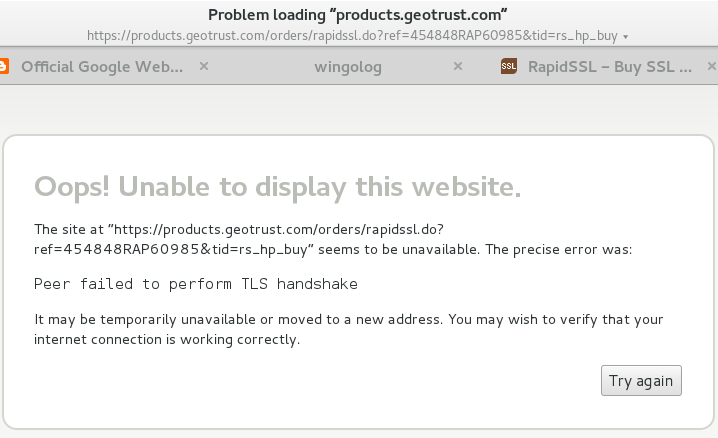

OK so you decide to pay for a certificate, assuming that will be better, and because who knows what's going on with StartSSL. You've heard of RapidSSL so you go to rapidssl.com. WTF their price is 49 dollars for a stupid certificate? Your domain name was only 10 dollars, and domain name resolution is an actual ongoing service, unlike certificate issuance that just happens one time. You can't believe it so you click through to the prices to see, and you get this:

Whatttttttttt

OK so I'm using Epiphany on Debian and I think that uses the system root CA list which is different from what Chrome or Firefox do but Jesus this is shaking my faith in the internet if I can't connect to an SSL certificate provider over SSL.

You remember hearing something on Twitter about cheaper certs, and oh ho ho, it's rapidsslonline.com, not just RapidSSL. WTF. OK. It turns out Geotrust and RapidSSL and Verisign are all owned by Symantec anyway. So you go and you pay. Paying is the first thing you have to do on rapidsslonline, before anything else happens. Welp, cross your fingers and take out your credit card, cause SSLanta Clause is coming to town.

Recall, distantly, that SSL has private keys and public keys. To create an SSL certificate you have to generate a key on your local machine, which is your private key. That key shouldn't leave your control -- that's why the DigitalOcean page is so bogus. The certification authority (CA) then needs to receive your public key and then return it signed. You don't know how to do this, because who does? So you Google and copy and paste command line snippets from a website. Whoops!

Hey neat it didn't delete your home directory, cool. Let's assume that your local machine isn't rooted and that your server isn't rooted and that your hosting provider isn't rooted, because that would invalidate everything. Oh what so the NSA and the five eyes have an ongoing program to root servers? Um, well, water under the bridge I guess. Let's make a key. You google "generate ssl key" and this is the first result.

# openssl genrsa -des3 -out foo.key 1024

Whoops, you just made a 1024-bit key! I don't know if those are even accepted by CAs any more. Happily if you leave off the 1024, it defaults to 2048 bits, which I guess is good.

Also you just made a key with a password on it (that's the -des3 part). This is eminently pointless. In order to use your key, your web server will need the decrypted key, which means it will need the password to the key. Adding a password does nothing for you. If you lost your private key but you did have it password-protected, you're still toast: the available encryption cyphers are meant to be fast, not hard to break. Any serious attacker will crack it directly. And if they have access to your private key in the first place, encrypted or not, you're probably toast already.

OK. So let's say you make your key, and make what's called the "CRTCSR", to ask for the cert.

# openssl req -new -key foo.key -out foo.csr

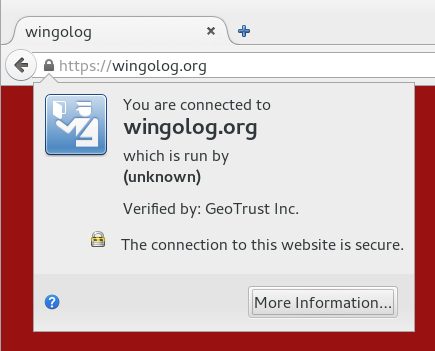

Now you're presented with a bunch of pointless-looking questions like your country code and your "organization". Seems pointless, right? Well now I have to live with this confidence-inspiring dialog, because I left off the organization:

Don't mess up, kids! But wait there's more. You send in your CSR, finally figure out how to receive mail for hostmaster@yourdomain.org because that's what "verification" means (not, god forbid, control of the actual web site), and you get back a certificate. Now the fun starts!

How are you actually going to serve SSL? The truly paranoid use an out-of-process SSL terminator. Seems legit except if you do that you lose any kind of indication about what IP is connecting to your HTTP server. You can use a more HTTP-oriented terminator like bud but then you have to mess with X-Forwarded-For headers and you only get them on the first request of a connection. You could just enable mod_ssl on your Apache, but that code is terrifying, and do you really want to be running Apache anyway?

In my case I ended up switching over to nginx, which has a startlingly underspecified configuration language, but for which the Debian defaults are actually not bad. So you uncomment that part of the configuration, cross your fingers, Google a bit to remind yourself how systemd works, and restart the web server. Haich Tee Tee Pee Ess ahoy! But did you remember to disable the NULL authentication method? How can you test it? What about the NULL encryption method? These are actual things that are configured into OpenSSL, and specified by standards. (What is the use of a secure communications standard that does not provide any guarantee worth speaking of?) So you google, copy and paste some inscrutable incantation into your config, turn them off. Great, now you are a dilettante tweaking your encryption parameters, I hope you feel like a fool because I sure do.

Except things are still broken if you allow RC4! So you better make sure you disable RC4, which incidentally is exactly the opposite of the advice that people were giving out three years ago.

OK, so you took your certificate that you got from the CA and your private key and mashed them into place and it seems the web browser works. Thing is though, the key that signs your certificate is possibly not in the actual root set of signing keys that browsers use to verify the key validity. If you put just your key on the web site without the "intermediate CA", then things probably work but browsers will make an additional request to get the intermediate CA's key, slowing down everything. So you have to concatenate the text files with your key and the one with the intermediate CA's key. They look the same, just a bunch of numbers, but don't get them in the wrong order because apparently the internet says that won't work!

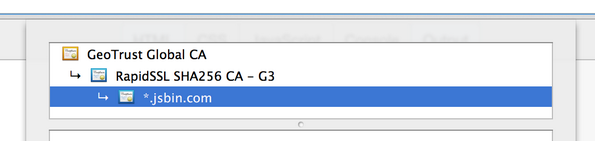

But don't put in too many keys either! In this image we have a cert for jsbin.com with one intermediate CA:

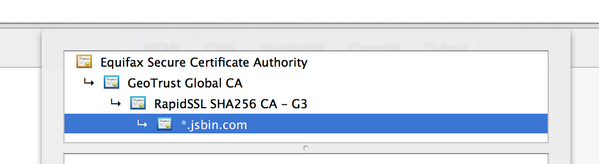

And here is the same but with an a different root that signed the GeoTrust Global CA certificate. Apparently there was a time in which the GeoTrust cert hadn't been added to all of the root sets yet, and it might not hurt to include them all:

Thing is, the first one shows up "green" in Chrome (yay), but the second one shows problems ("outdated security settings" etc etc etc). Why? Because the link from Equifax to Geotrust uses a SHA-1 signature, and apparently that's not a good idea any more. Good times? (Poor Remy last night was doing some basic science on the internet to bring you these results.)

Or is Chrome denying you the green because it was RapidSSL that signed your certificate with SHA-1 and not SHA-256? It won't tell you! So you Google and apply snakeoil and beg your CA to reissue your cert, hopefully they don't charge for that, and eventually all is well. Chrome gives you the green.

Or does it? Probably not, if you're switching from a web site that is also available over HTTP. Probably you have some images or CSS or Javascript that's being loaded over HTTP. You fix your web site to have scheme-relative URLs (like //wingolog.org/ instead of http://wingolog.org/), and make sure that your software can deal with it all (I had to patch Guile :P). Update all the old blog posts! Edit all the HTMLs! And finally, green! You're golden!

Or not! Because if you left on SSLv3 support you're still broken! Also, TLSv1.0, which is actually greater than SSLv3 for no good reason, also has problems; and then TLS1.1 also has problems, so you better stick with just TLSv1.2. Except, except, older Android phones don't support TLSv1.2, and neither does the Googlebot, so you don't get the rankings boost you were going for in the first place. So you upgrade your phone because that's a thing you want to do with your evenings, and send snarky tweets into the ether about scumbag google wanting to promote HTTPS but not supporting the latest TLS version.

So finally, finally, you have a web site that offers HTTPS and HTTP access. You're good right? Except no! (Catching on to the pattern?) Because what happens is that people just type in web addresses to their URL bars like "google.com" and leave off the HTTP, because why type those stupid things. So you arrange for http://www.wobsite.com to redirect https://www.wobsite.com for users that have visited the HTTPS site. Except no! Because any network attacker can simply strip the redirection from the HTTP site.

The "solution" for this is called HTTP Strict Transport Security, or HSTS. Once a visitor visits your HTTPS site, the server sends a response that tells the browser never to fetch HTTP from this site. Except that doesn't work the first time you go to a web site! So if you're Google, you friggin add your name to a static list in the browser. EXCEPT EVEN THEN watch out for the Delorean.

And what if instead they go to wobsite.com instead of the www.wobsite.com that you configured? Well, better enable HSTS for the whole site, but to do anything useful with such a web request you'll need a wildcard certificate to handle the multiple URLs, and those run like 150 bucks a year, for a one-bit change. Or, just get more single-domain certs and tack them onto your cert, using the precision tool cat, but don't do too many, because if you do you will overflow the initial congestion window of the TCP connection and you'll have to wait for an ACK on your certificate before you can actually exchange keys. Don't know what that means? Better look it up and be an expert, or your wobsite's going to be slow!

If your security goals are more modest, as they probably are, then you could get burned the other way: you could enable HSTS, something could go wrong with your site (an expired certificate perhaps), and then people couldn't access your site at all, even if they have no security needs, because HTTP is turned off.

Now you start to add secure features to your web app, safe with the idea you have SSL. But better not forget to mark your cookies as secure, otherwise they could be leaked in the clear, and better not forget that your website might also be served over HTTP. And better check up on when your cert expires, and better have a plan for embedded browsers that don't have useful feedback to the user about certificate status, and what about your CA's audit trail, and better stay on top of the new developments in security! Did you read it? Did you read it? Did you read it?

It's a wonder anything works. Indeed I wonder if anything does.